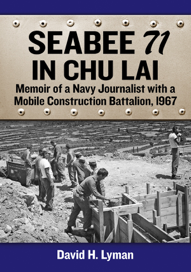

The Book:

SEABEE71

IN CHU LAI

A 350 page memoir of a Navy Journalist's 14 months with the Seabees.

Photographs and text copyright © 1967 and 2019 by David H. Lyman

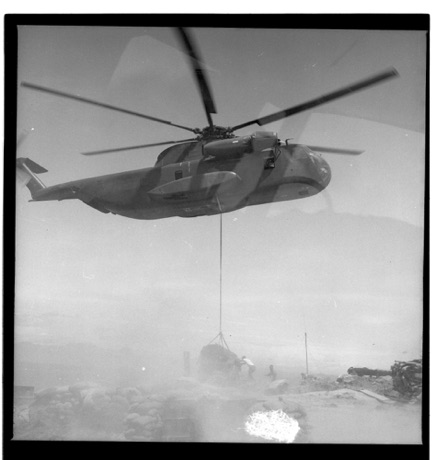

“They’re going to be using helicopters to set the concert bases,” the XO added. “Some of the towers are located in unaccessible places. We’ll build a few towers here, then delivery them by flying crane. Should make for some interesting photographs. LTJG Powers is in charge. Coordinate with him, and take Widmark with you.” Tom Widmark was the unit’s photography assistant. He was a really an EO3, who had been coerced by the CO into moving from Alpha over to Headquarters Company. We did have a First Class Photographer’s Mate on board, Knapp, who, Tuffy Lake told me, had a fear of flying and would not go up in a helicopter to make aerial images, so Tom wound up making and processing most of the construction progress pictures.

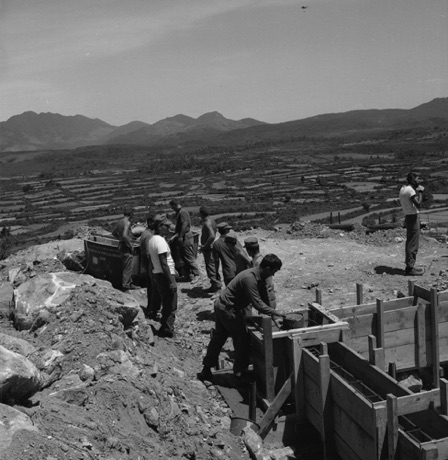

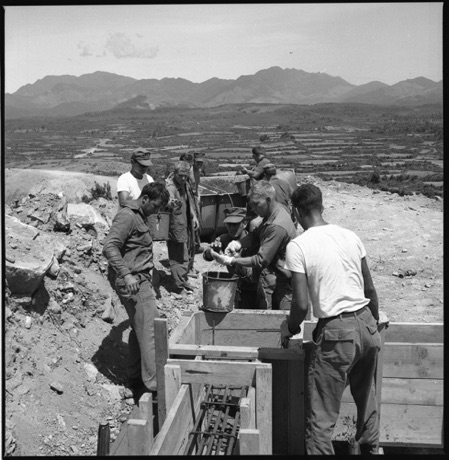

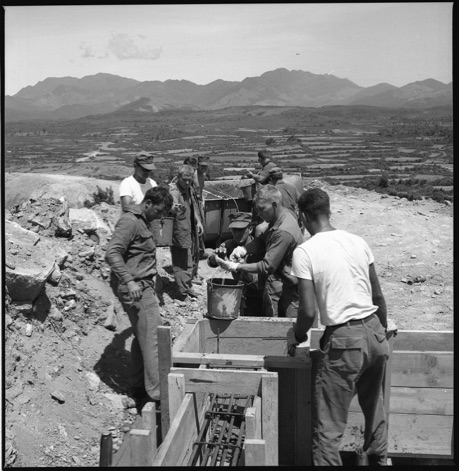

The order for the towers had come down from Regiment headquarters in DaNang: The Army, now guarding the Chu Lai complex, wanted seven 60-foot towers placed along the perimeter. These towers had proven useful in spotting Charlie's movements up near the DMZ—so the Army wanted them here. Each tower was fitted with a top deck, surrounded by sandbags to protect the observers on duty from snipers, and with a tin roof overhead. They were designed to stand with one leg shot away. The access ladder to the top deck was inside a corrugated steel conduit, to shield the guards climbing up and down.

Five of the seven towers were straight-forward projects, their locations accessible by truck, so the tower bases and the towers themselves were constructed onsite, the towers themselves, raised into place with Seventy-One’s crane.

Towers 6 and 7 were another story. Tower 6, overlooking the Tra Bong River was so far off in the bushes, trucks could not delivery building materials; Tower 7 was on the top of Signal Hill, only a mountain goat, or a Marine, could climb. What to do?

The Operations Officer, Naval Civil Engineer LCDR Martin, made a few phone calls, first to the Army and then to the US Marines.

“Could we borrow the use of a helicopter or two,” he asked each. “Ouch!” he said when he was told the price—$1,600 an hour. “I need to ferry buckets of wet concrete to inaccessible locations for your observation towers, then fly in the towers themselves.” He got an okay, and a schedule was arranged.

On Tower 6 near the village Tan Ka, the crew enlisted the local village kids into a bucket brigade to return the empty pails back to the container. Slave labor? No, the kids were overjoyed to help the big American guys, and in return got candy bars and cans of C-ration. Once the forms had set, these bases would support the massive 60-foot observation towers.